WILDERNESS PSYCHOLOGICAL FIRST AID

Mental Health First Aid Services

| PROVIDER | PHONE | WEB |

|---|---|---|

| Lifeline Australia | 131114 | https://www.lifeline.org.au |

| Lifeline New Zealand | 0800543354 | https://www.lifeline.org.nz |

| Kids Helpline | 1800551800 | https://kidshelpline.com.au |

| MensLine Australia | 1300789978 | https://www.mensline.org.au/ |

| Suicide Call Back Service | 1300659467 | https://www.suicidecallbackservice.org.au/ |

| Beyond Blue | 1300224636 | https://www.beyondblue.org.au/ |

| Open Arms - Veterans & Family Counselling | 1800011046 | https://www.openarms.gov.au/ |

State Crisis Numbers

| STATE | PHONE | PROVIDER |

|---|---|---|

| NSW | 1800011511 | Mental Health Line |

| VIC | 1300651251 | Suicide Help Line |

| QLD | 13432584 | 13 HEALTH |

| TAS | 1800332388 | Mental Health Services Helpline |

| SA | 131465 | Mental Health Assessment and Crisis Intervention Service |

| WA | 1300555788 | Mental Health Emergency Response Line |

| NT | 1800682288 | Mental Health Line |

| ACT | 1800629354 | Mental Health Triage Service |

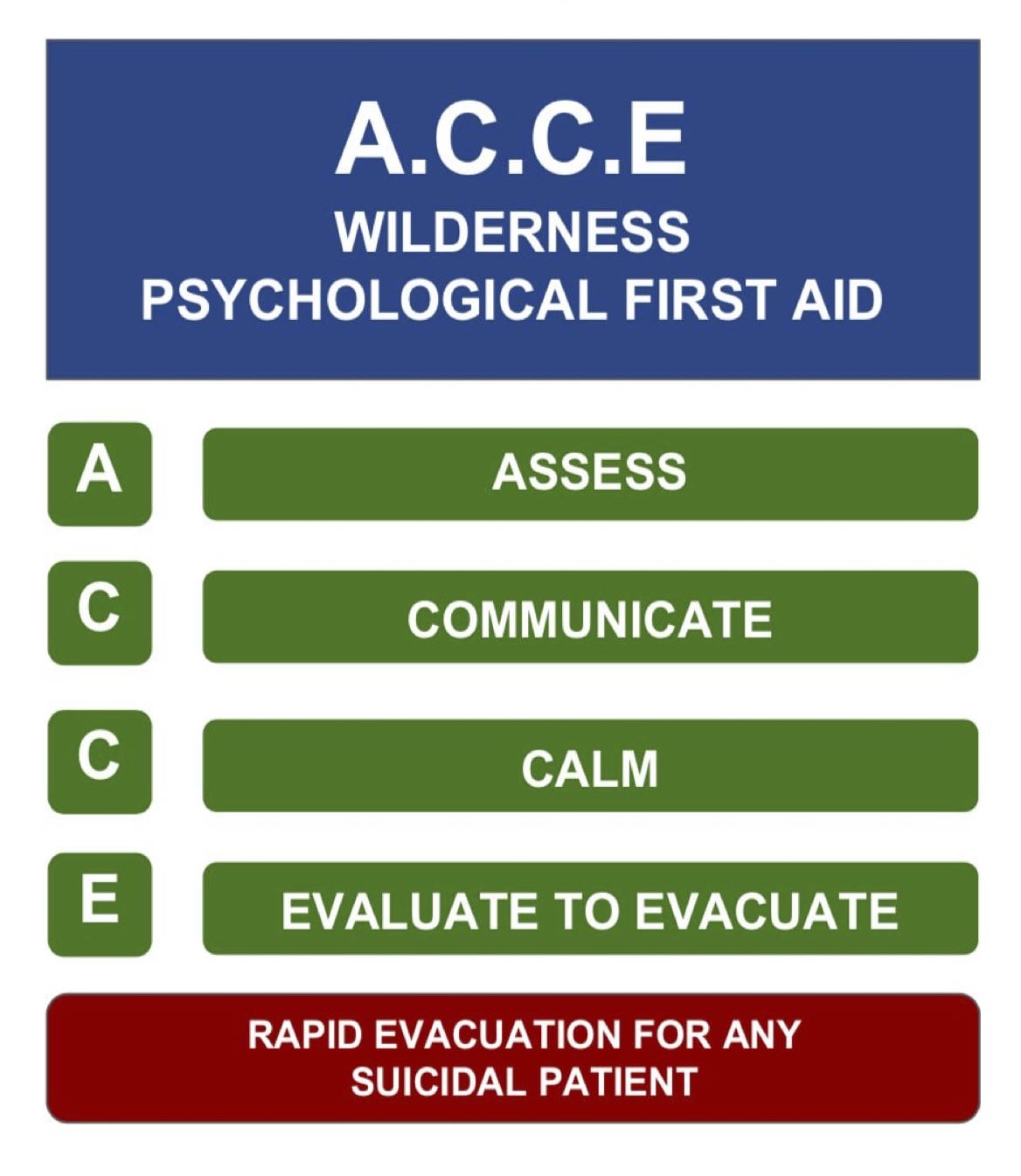

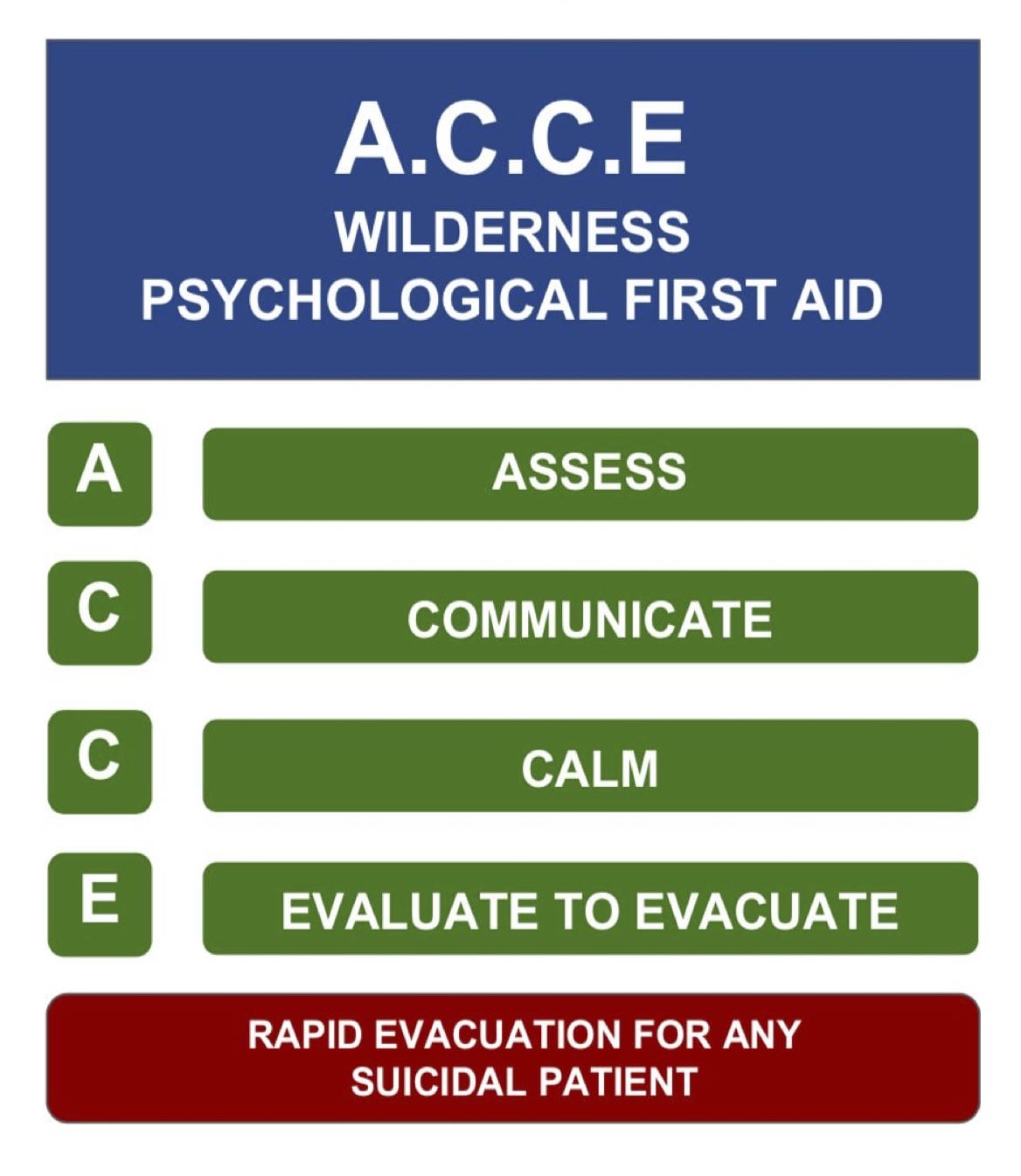

The A.C.C.E Model

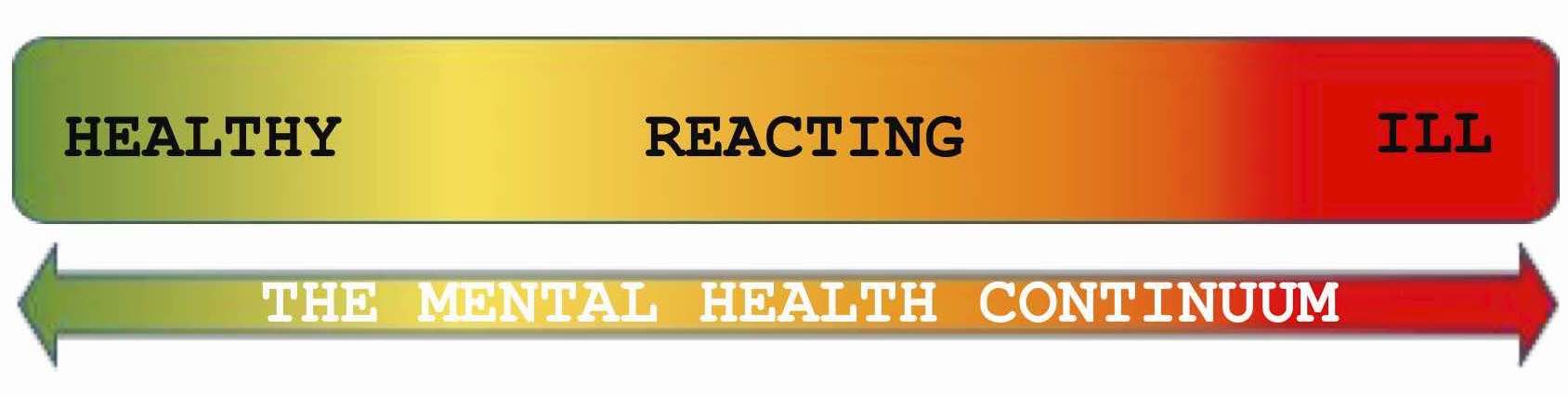

The Mental Health Continuum

When using the “A.C.C.E’ Model, keep it simple

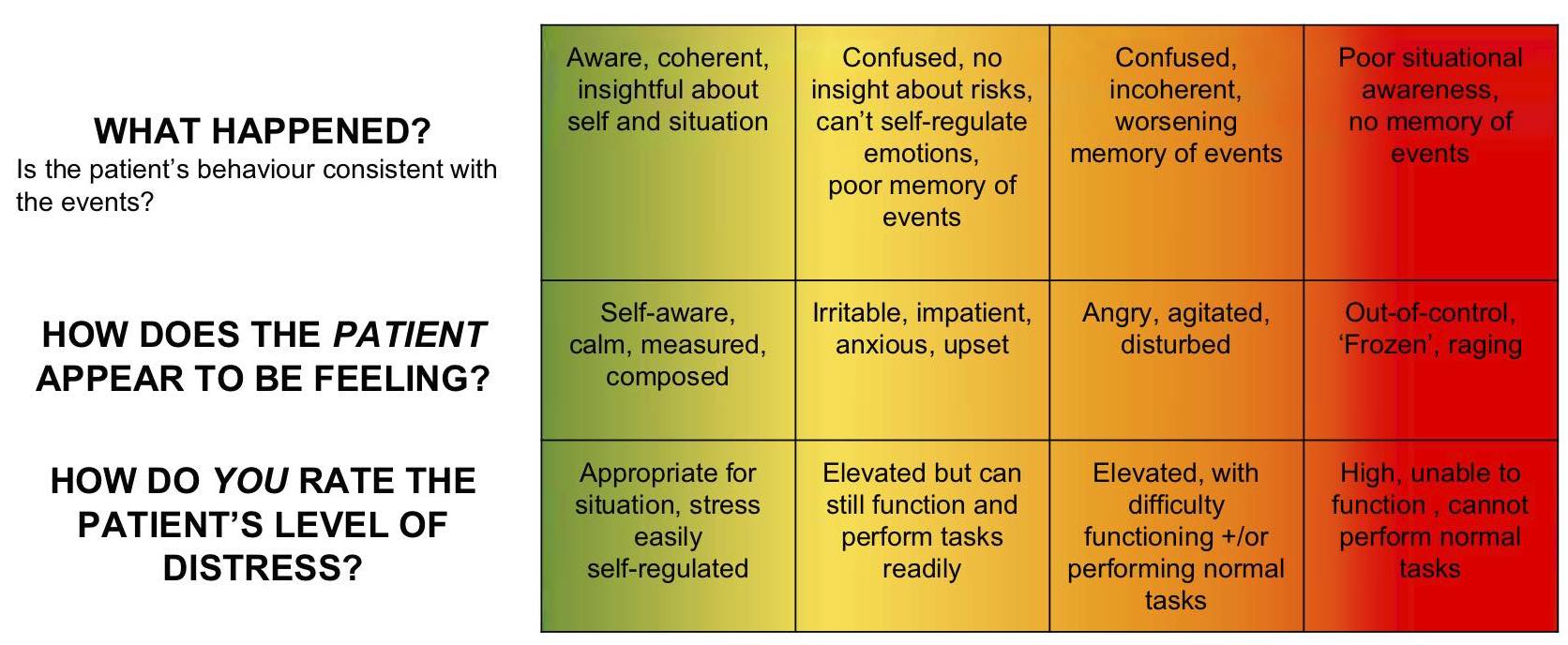

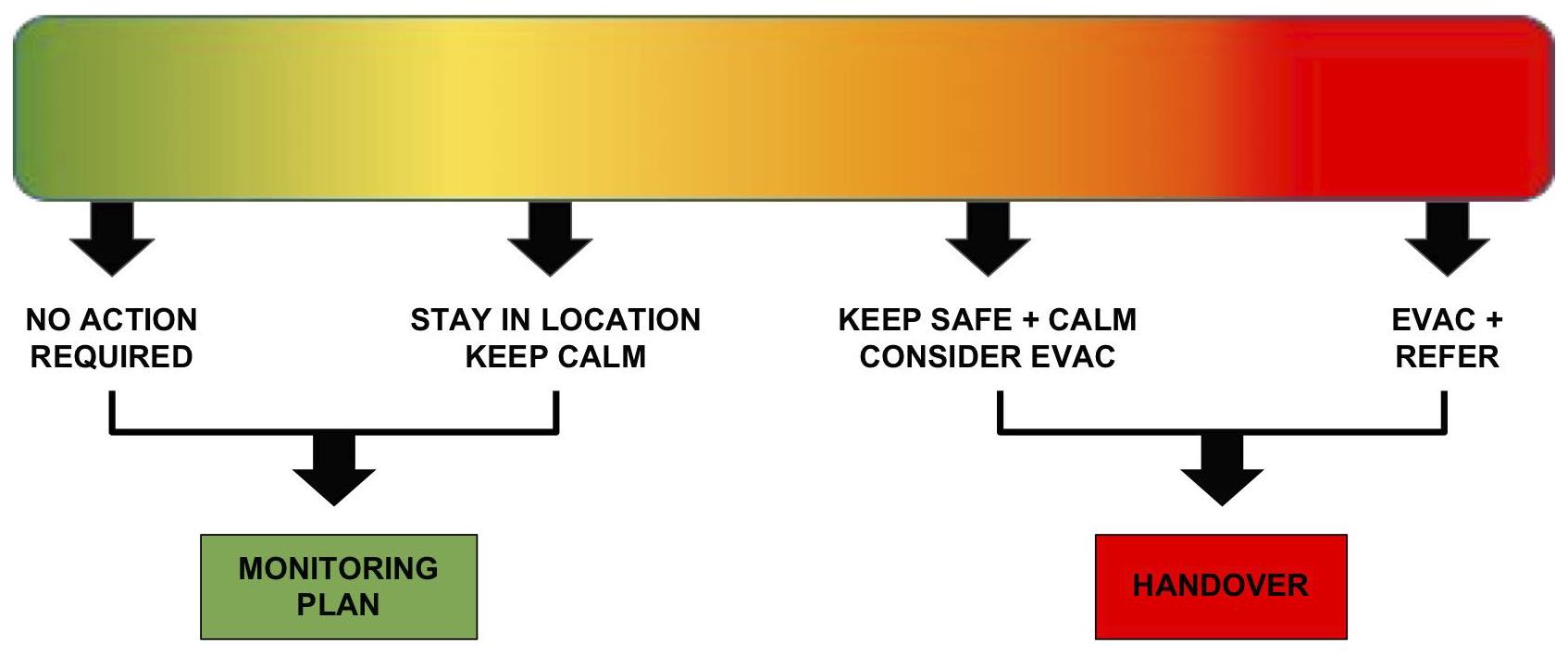

What we’re really looking for when using this assessment tool is whether the patient/incident is closer to GREEN, or closer to RED.

Assess: Individual

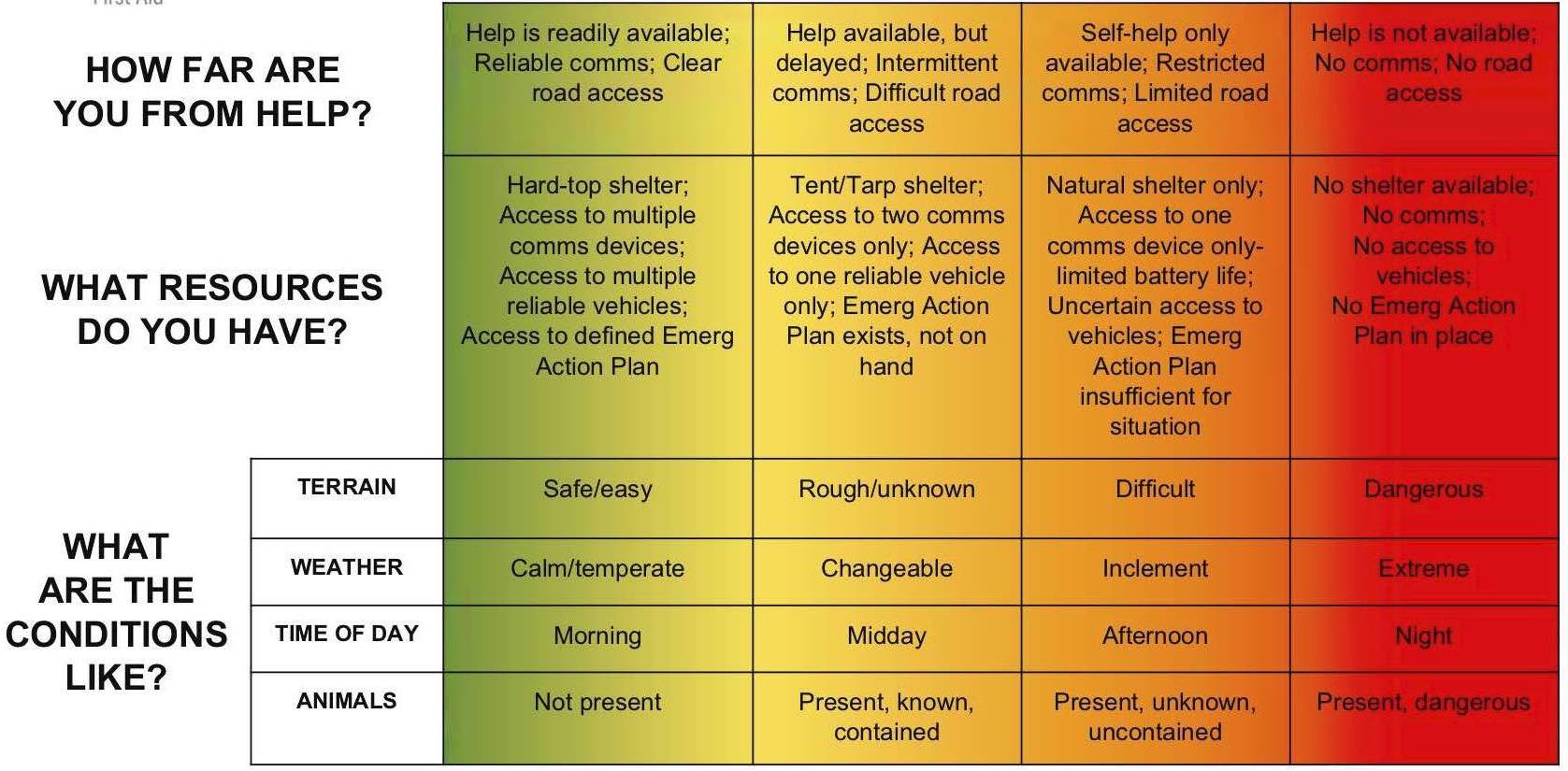

Assess: Environment

Assess: Group

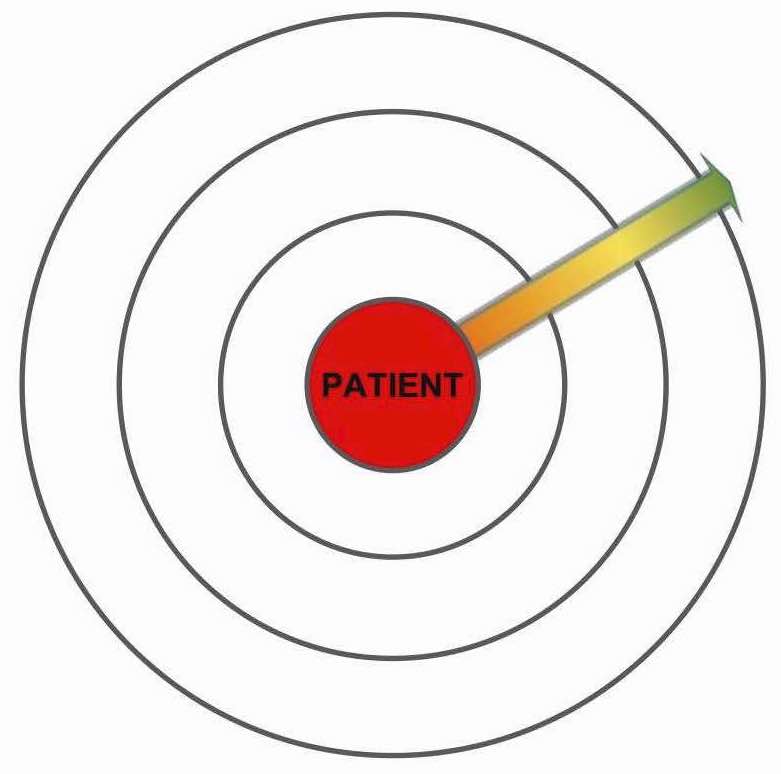

Think of the GROUP (i.e. those under your duty of care) as a bullseye with the PATIENT/INCIDENT at the center and group members at various distances according to their exposure.

Questions:

- Where to various group members get placed on the bullseye?

- What requirements do they have (e.g. medical, food, shelter)

- Do the total group requirements outweigh your resources

Communicate

Reassurance

Reassure the patient that they are safe and that their emotions are normal for the situation

Communication + Interaction Style

- Introduce yourself with your name and your role

- Keep your words clear, concise, simple and calm

- Maintain an even tone and pace of speech; don't raise your voice

- Give regular updates to the patient about what is happening in the situation

- Be non-judgemental, and demonstrate active listening

- Use age-appropriate language

- Maintain good eye contact

- Be patient

Physical Space

- Move the patient away from distressing sights

- Keep children with parents/caregivers where possible

- Your physical proximity to the patient largely depends on the situation and person – however, if you are unsure or wary (or if the patient is displaying high levels of agitation/aggression) don’t get too close and don’t restrict their movement

Calm

Breathing

- The aim here is to slow their breathing.

- You can try the following technique: breathe in through the nose for 4 seconds, breathe out through the nose for 4 seconds. Continue until the body settles.

- If the patient is having a panic attack or hyperventilating, try the same technique. It may also help to breathe and count with them to demonstrate the pace and depth of the breath

Grounding

The aim here is to focus the patient on tangible things. You can try the following technique:

- Identify 4 things you can see, 4 things you can hear, and 4 things you can feel

- Identify 3 things you can see, 3 things you can hear, and 3 things you can feel

- Identify 2 things you can see, 2 things you can hear, and 2 things you can feel

- Identify 1 thing you can see, 1 thing you can hear, and 1 thing you can feel

Distraction

- The aim here is to get the patient thinking about something other than the incident/their condition

- Talk to the patient and ask them questions about their interests/hobbies/experiences/familiy/pets, etc

- Give the patient a simple physical/behavioural tasks (eg: hold onto a rope, roll up bandages, calm someone else, help setup/take down a tent, etc.)

Eval to Evac

Monitor +/ or Handover

Monitor

- Trigger

- What caused the incident?

- Treatment

- What did you do that worked?

- Tomorrow

- How are you going to implement the effective treatment going forward?

Handover

- Incident

- Brief description of what happened.

- Signs & Symptoms

- How the patient presented to you; what you noticed.

- Treatment

- What did you do for them? How did they respond?

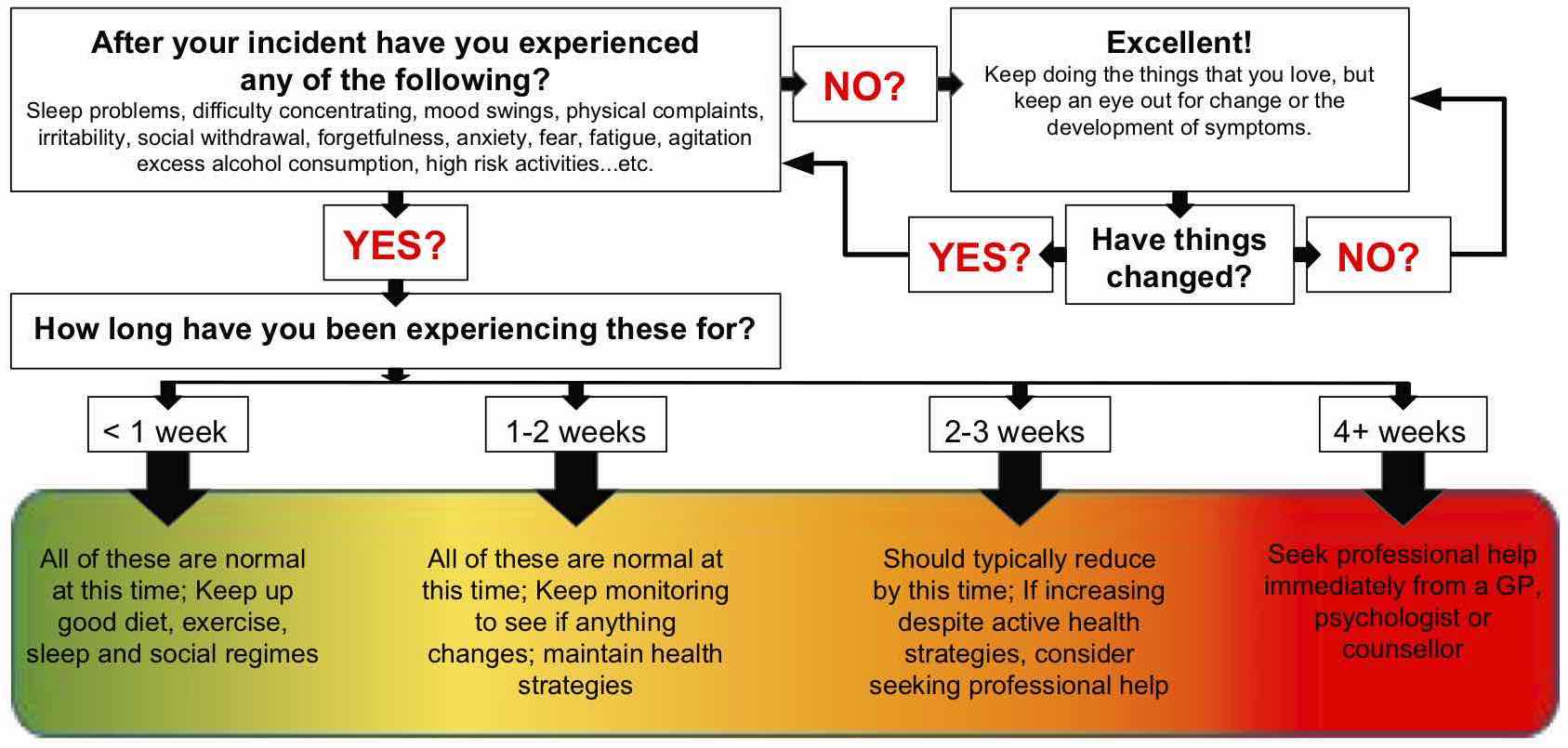

Self Care

Notes

Notes about the A.C.C.E Model

- This model is adaptable to almost any remote or wilderness situation, regardless of the length of time or distance from resources.

- Focus of the model is situational management rather than individual support

- Designed from evidence-based research into critical incidents and management of patients with psychological presentations

- Remember: the aim of PFA is to keep the patient calm and safe until further help arrives.

Resources

The following resources are from: https://www.cci.health.wa.gov.au/Resources/Looking-After-Others

What is anxiety?

Many people experiencing the symptoms of anxiety can begin to wonder if there is something really wrong with them. One typical fear is that they might be going crazy. Unfortunately, the reactions and comments from other people such as, ‘just get yourself together’ are not very helpful.

Although you might feel alone in your struggle against anxious moods, the reality is that many people experience these moods either from time to time, or on a more regular basis. In fact, it is estimated that 1 in every 5 experience significantly anxious mood at some time in their life.

Anxiety can effect any kind of person at any stage of their life, whether they are an introvert or an extrovert, socially active or shy, youthful or elderly, male or female, wealthy or poor. Whatever your distinction, you can become anxious. That means that any person you know is also fair game. So remember, you are not alone.

Understanding Anxiety

Feeling afraid is very much a part of the experience of being human. It occurs in response to realistically anticipated danger and therefore is a survival instinct. For example, if a ferocious animal confronted us it is likely that we would respond with fear. This response is important because it initiates a whole series of physical and behavioural changes that ultimately serve to protect us. In this example, when confronted by an animal, the feeling of fear would probably lead us to either run for our lives or become sufficiently ‘pumped up’ to physically defend ourselves. As you can see from this example, the experience of fear is part of a process of survival.

The experience of anxiety is very similar to the experience of fear - the main difference is that anxiety occurs in the absence of real danger. That is, the individual may think that they are in danger but the reality is that they are not. To illustrate this, think of the anxiety one may feel when walking down a poorly lit alley. The individual may feel anxious because they perceive some potential danger. This may not mean that there is any real danger in walking down this particular alley, but what causes the experience of anxiety is that the person believes that they are in danger. Therefore, the experience of anxiety and fear are basically the same except that in the case of anxiety, there may not be any actual danger - the person just thinks there is.

Fight/Flight Response

It is important to fully understand the way our bodies react to threat or danger, whether real or imagined. When a person is in danger, or believes that they are in danger a number of changes occur. This response has been named the fight/flight response. As previously explained, when confronted with danger we will typically flee from the situation, or stand and fight. The main purpose of the fight/flight response is to protect the individual. It is therefore important to remember that the experience of anxiety is not in itself, harmful. When a person’s fight/flight response is activated, three major systems are affected. These are the physical, cognitive and behavioural systems.

Physical System

When we believe that we are in danger, our whole physical system undergoes some major, temporary changes designed to enhance our ability to either run away, or stand and be ready to fight. Physically, as soon as danger is perceived, the brain sends a message to our autonomic nervous system. Our autonomic nervous system has two sections: the sympathetic branch and the parasympathetic branch. These two sections control the physical changes that occur in the fight/flight response. The sympathetic branch is the part that activates the various areas of the body to be ready for action. When the sympathetic branch is activated, it includes all areas of the body, and therefore, the person experiences physical changes from head to toe. To get things moving, the sympathetic nervous system releases two chemicals from the adrenal glands on the kidneys. These chemicals are called adrenalin and noradrenalin and are basically messengers that serve to maintain the physical changes for a sufficient amount of time. So what are these physical changes that the sympathetic mechanism produces when you are anxious?

- An increase in heart rate and strength of beat. One physical change that is quite noticeable to the person experiencing the fight/flight response, is an increase in heart rate and the strength of heartbeat. An increase in heart rate enables blood to be pumped around the body faster, so that oxygen gets delivered more promptly to the various tissues of the body and waste products can be efficiently eliminated.

- A redistribution of blood from areas that aren’t as vital to those that are. There is also a change in blood flow - away from places where it is not needed (such as skin, fingers and toes) towards the places it is likely to be needed (large organs and muscles). This is very useful because if we were attacked and cut in some way we would be less likely to bleed to death, as the blood will be with the vital organs. This physical change results in the skin looking pale and feeling cold, and also in the experience of cold, numb and tingling fingers and toes.

- An increase in the rate and depth of breathing. As well as changes to heart rate, there are also changes to the speed and depth of breathing. This is very important, as it provides the tissues with the extra amount of oxygen required to prepare for action. The feelings produced by this increase in breathing can include breathlessness, choking or smothering feelings, tightness and pain in the chest, and sighing and yawning. One of the main side effects of this increase in breathing is that the blood supply to the head is actually decreased. This is not dangerous but can produce a collection of unpleasant symptoms, including: dizziness, light-headedness, blurred vision, confusion, feelings of unreality and hot flushes.

- An increase in sweating. Another physical change in the fight/flight response is an increase in sweating. This causes the body to become more slippery, making it harder for a predator to grab, and also cooling the body and thus preventing it from overheating.

- Widening of the pupils of the eyes. One effect of the fight/flight response that people are often unaware of, is that the pupils widen to let in more light, which may result in the experience of blurred vision, spots before the eyes, or just a sense that the light is too bright. This change enables the person to more effectively use their sight to identify any hidden dangers such as something lurking in the shadows.

- Decreased activity of the digestive system. The decreased activity of the digestive system allows more energy to be diverted to systems more immediately related to fight or flight. The range of effects you might notice as a result of this body change are a decrease in salivation, resulting in a dry mouth and decreased activity in the digestive system, often producing feelings of nausea, a heavy stomach or even constipation.

- Muscle tension. Finally, many of the muscle groups tense up in preparation for fight/flight and this results in subjective feelings of tension, sometimes resulting in aches and pains and trembling and shaking. The whole physical process is a comprehensive one that often leaves the individual feeling quite exhausted.

Behavioural System

As already mentioned, the two main behaviours associated with fear and anxiety are to either fight or flee. Therefore, the overwhelming urges associated with this response are those of aggression and a desire to escape, wherever you are. Often this is not possible (due to social constraints) and so people often express the urges through behaviours such as foot tapping, pacing or snapping at people.

Cognitive System

As the main objective of the fight/flight response is to alert the person to the possible existence of danger, one major cognitive change is that the individual begins to shift their attention to the surroundings to search for potential threat. This accounts for the difficulty in concentrating that people who are anxious experience. This is a normal and important part of the fight/flight response as its purpose is to stop you from attending to your ongoing chores and to permit you to scan your surroundings for possible danger. Sometimes an obvious threat cannot be found. Unfortunately, most of us cannot accept not having an explanation for something and end up searching within themselves for an explanation. This often results in people thinking that there is something wrong with them - they must be going crazy or dying.

Restoration of the Systems

Once the immediate danger has abated, the body begins a process of restoration back to a more relaxed state. This is once again controlled by the autonomic nervous system. This time it instructs the parasympathetic branch to begin the process of counteracting the sympathetic branch. As a result, the heart rate begins to slow, breathing rate slows, the body’s temperature begins to lower and the muscles begin to relax. Part of the process of restoration is that the systems do not return to normal straight away. Some arousal continues and this is for a very good reason. In primitive times, if a wild animal confronted us it would be foolish to relax and be off guard as soon as the animal began to back off. The chances of danger continuing in such a case causes the body to remain prepared for the need to once again face danger. Therefore, some residual effects of the fight/flight response remain for some time and only gradually taper off. This can leave the individual feeling ‘keyed up’ for some time afterwards. This helps to understand why it is that people can feel anxious for ongoing periods of time when no obvious stressor is present.

What Causes Anxiety?

The combination of factors which result in an individual developing an anxiety disorder differ from person to person. However, there are some major factors that have been identified, which may be common to sufferers. These factors can be effectively divided into biological and psychological causes.

Biological Factors

A genetic factor has been linked to the development of anxiety disorders. For example, in obsessive-compulsive disorder, about 20% of first-degree relatives have also suffered from the condition. Overall, based on family studies, it has been suggested that individuals may inherit a vulnerability to developing an anxiety disorder.

Psychological Factors

Having this genetic vulnerability does not imply that those individuals will develop an anxiety disorder. A great deal depends on the lifestyle of that person, the types of life stressors they have encountered and their early learning. For example, if we were taught to fear certain neutral situations as a child it can become difficult to extinguish these learned patterns of behaviour. Therefore, we may have developed certain patterns of thinking and behaving which contribute to the development of an anxiety disorder.

Summary

As you can see from this description of the fight/flight response, anxiety is an important emotion that serves to protect us from harm. For some people the fight/flight response becomes activated in situations where no real danger is present. The types of situations vary greatly from person to person. For example, simply anticipating poor performance on an examination can be enough to activate the fight/flight response. An anxiety disorder is usually diagnosed when a person cannot manage to function adequately in their daily life due to the frequency and severity of the symptoms of anxiety. It is important to keep in mind however, that some anxiety is functional, enabling us to get to work on time, meet demands, cross busy streets and remain aware of our surroundings.

Coping with Stress

Stress and Stressors

Stress is something that is part of normal life, in that it is experienced by everyone from time-to-time. However, some people suffer from stress which is so frequent or so severe that it can seriously impact on their quality of life. Stress can come from a huge range of sources (stressors), such as:

- Relationships with others

- Work-related issues

- Study demands

- Coping with illness

- Life changes, such as marriage, retirement, divorce

- Day-to-day activities and tasks

- Positive events, such as organising holidays or parties

- Juggling many roles or tasks at the same time Some people are aware of what tends to trigger their stress, and this increases their ability to either prevent stress or to handle it more effectively. Many others are less able to deal with stress, and identifying stressors is a key step in this. If you often experience stress, take some time to consider what tends to set it off for you.

Symptoms of Stress

Some people do not even notice that they are stressed until symptoms begin to occur, including:

- Irritability or moodiness

- Interrupted sleep

- Worrying or feeling of anxiety

- Back and neck pain

- Frequent headaches, minor to migraine

- Upset stomach

- Increased blood pressure

- Changes in appetite

- Rashes or skin breakouts

- Chest pains

- Making existing physical problems worse

- More susceptible to cold/flu and slower recovery These symptoms reduce quality of life, and people suffering from stress may notice that work performance or relationships suffer more as a result. You may be able to use some the strategies listed here, or you may find it useful to consult a professional for more help.

Stress Management Tips

- Identify your stressors, and see if there are some things within your control to manage better. Some things will be beyond your control, for example if you work a job that is based on working towards deadlines then you can’t change this without changing jobs. But perhaps you can control some aspects, such as scheduling to have at least a short lunch break each day, or to go to bed earlier so that you have more energy to cope with the daytime.

- Build regular exercise into your life - as well as being part of a healthy , balanced lifestyle and giving you more energy, many people find that working out at the gym or playing sport helps them to unwind.

- Make sure that you eat and sleep well.

- Take time out for family, friends and recreational activities. Most of us know that this is important but we do not all do it. If you find it hard to make time for this, perhaps you need to take deliberate steps to have time out, such as set aside one evening a week where you meet up with friends or enjoy a hobby, or set aside one day of the weekend for relaxing at home.

- Problem-solving techniques can be a useful way of clarifying the problem, brainstorming possible solutions, and then choosing one to put into action after listing the pros and cons of each option. See the handout Problem Solving for more details about this.

- Learn calming techniques such as controlled breathing and progressive muscle relaxation, to train your mind and body to become more relaxed. These techniques require practice but can be helpful with regular use. See handouts Calming Technique and Progressive Muscle Relaxation.

- You may wish to speak to a professional about assertiveness training and communication skills which can help you to deal with challenging situations more effectively, thereby reducing stress. See the handout Assertive Communication.

- Last but definitely not least, consider whether there is negative thinking which is contributing to your stress. Negative thinking can make us worry more than is necessary, increasing stress, and generally does not motivate us to take positive actions. See the handouts Thinking & Feeling, Analysing Your Thinking and Changing Your Thinking.

What is Panic?

To understand panic, we need to understand fear. You can think of fear as an automatic alarm response that switches on the moment there is danger. Think about what would happen to you if a dangerous animal approached you. For most people it would be panic stations! You, and almost everyone, would go through a whole series of bodily changes, like your heart pumping, breathing faster, sweating, all in order to respond to the danger in front of you. This alarm response would probably lead us to either run for our lives or become sufficiently ‘pumped up’ to physically defend ourselves. This alarm response is an important survival mechanism called the fight or flight response.

Sometimes, however, it is possible to have this intense fear response when there is no danger – it is a false alarm that seems to happen when you least expect it. It is like someone ringing the fire alarm when there is no fire! Essentially, a panic attack is a false alarm.

Many people experience some mild sensations when they feel anxious about something, but a panic attack is much more intense than usual. A panic attack is usually described as a sudden escalating surge of extreme fear. Some people portray the experience of panic as ‘sheer terror’. Let’s have a look at some of the symptoms of a panic attack:

Panic Attack Symptoms

- Skipping, racing or pounding heart

- Sweating

- Trembling or shaking

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

- Choking sensations

- Chest pain, pressure or discomfort

- Nausea, stomach problems or sudden diarrhoea

- Dizziness, lightheadedness, feeling faint

- Tingling or numbness in parts of your body

- Hot flushes or chills

- Feeling things around you are strange, unreal, detached, unfamiliar, or feeling detached from body

- Thoughts of losing control or going crazy

- Fear of dying

As you can see from the list, many of the symptoms are similar to what you might experience if you were in a truly dangerous situation. A panic attack can be very frightening and you may feel a strong desire to escape the situation. Many of the symptoms may appear to indicate some medical condition and some people seek emergency assistance.

Characteristics of a Panic Attack

- It peaks quickly - between 1 to 10 minutes

- The apex of the panic attack lasts for approximately 5 to 10 minutes (unless constantly rekindled)

- The initial attack is usually described as “coming out of the blue” and not consistently associated with a specific situation, although with time panics can become associated with specific situations

- The attack is not linked to marked physical exertion

- The attacks are recurrent over time

- During an attack the person experiences a strong urge to escape to safety

Many people believe that they may faint whilst having a panic attack. This is highly unlikely because the physiological system producing a panic attack is the opposite of the one that produces fainting. Sometimes people have panic attacks that occur during the night when they are sleeping. They wake from sleep in a state of panic. These can be very frightening because they occur without an obvious trigger. Panic attacks in, and of themselves, are not a psychiatric condition. However, panic attacks constitute the key ingredient of Panic Disorder if the person experiences at least 4 symptoms of the list previously described, the attacks peak within about 10 minutes and the person has a persistent fear of having another attack.

Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia

Someone with panic disorder has a persistent fear of having another attack or worries about the consequences of the attack. Many people change their behaviour to try to prevent panic attacks. Some people are affected so much that they try to avoid any place where it might be difficult to get help or to escape from. When this avoidance is severe it is called Agoraphobia.

Panic Disorder is more common than you think. A recent study reported that 22.7% of people have reported experience with panic attacks in their lifetime. 3.7% have experienced Panic Disorder and 1.1% have experienced Panic Disorder plus Agoraphobia. * These numbers equate to millions of people world wide. If left untreated, Panic Disorder may become accompanied by depression, other anxiety disorders, dependence on alcohol or drugs and may also lead to significant social and occupational impairment.

Biology and Psychology of Panic

Panic attacks (the key feature of Panic Disorder) can be seen as a blend of biological, emotional & psychological reactions. The emotional response is purely fear. The biological & psychological reactions are described in more detail below.

Biological Reactions 1: Fight or Flight

When there is real danger, or when we believe there is danger, our bodies go through a series of changes called the fight/flight response. Basically, our bodies are designed to physically respond when we believe a threat exists, in case we need to either run away, or stand and fight. Some of these changes are:

- an increase in heart rate and strength of heart beat. This enables blood and oxygen to be pumped around the body faster.

- an increase in the rate and depth of breathing. This maintains oxygen and carbon dioxide levels.

- an increase in sweating. This causes the body to become more slippery, making it harder for a predator to grab, and also cooling the body.

- muscle tension in preparation for fight/flight. This results in subjective feelings of tension, sometimes resulting in aches and pains and trembling and shaking. When we become anxious and afraid in situations where there is no real danger, our body sets off an automatic biological “alarm”. However, in this case it has set off a “false alarm”, because there is no danger to ‘fight’ or run from.

Biological Reactions 2: Hyperventilation & Anxious Breathing

When we breathe in we obtain oxygen that can then be used by the body, and we breathe out to expel the product of our metabolic processes - carbon dioxide. The body naturally maintains optimal levels of both oxygen and carbon dioxide. When we are anxious, the optimal level of carbon dioxide is disrupted because we begin to hyperventilate, or breathe too much. If the body cannot return carbon dioxide levels to the optimal range, we experience further symptoms such as dizziness, light-headedness, headache, weakness and tingling in the extremities, and muscle stiffness. For people with panic, these physiological sensations can be quite distressing, as they may be perceived as being a sign of an oncoming attack, or something dangerous such as a heart attack. However these are largely related to the fight or flight response and overbreathing, not physical problems.

Psychological Reactions 1: Thinking Associated with Panic

We’ve described the physical symptoms of panic. People who panic are very good at noticing these symptoms. They constantly scan their bodies for these symptoms. This scanning for internal sensations becomes an automatic habit. Once they have noticed the symptoms they are often interpreted as signs of danger. This can result in people thinking that there is something wrong with them, that they must be going crazy or losing control or that they are going to die. There are a number of types of thinking that often occur during panic, including:

- Catastrophic thoughts about normal or anxious physical sensations (eg “My heart skipped a beat - I must be having a heart attack!”)

- Over-estimating the chance that they will have a panic attack (eg “I’ll definitely have a panic attack if I catch the bus to work”)

- Over-estimating the cost of having a panic attack: thinking that the consequences of having a panic attack will be very serious or very negative.

Psychological Reactions 2: Behaviours that Keep Panic Going

When we feel anxious or expect to feel anxious, we often act in some way to control our anxiety. One way you may do this is by keeping away from situations where you might panic. This is called avoidance, and can include:

- Situations where you’ve had panic attacks in the past

- Situations from which it is difficult to escape, or where it might be difficult to get help, such as public transport, shopping centres, driving in peak hour traffic

- Situations or activities which might result in similar sensations, such as physical activity, drinking coffee, having sex, emotional activities such getting angry

A second response may be to behave differently, or to use “safety behaviours”. The following are examples of these; you might make sure you are near an escape route, carry medication with you, or ensure that you are next to a wall to lean on. Or you may use other more subtle methods like trying to distract yourself from your anxiety by seeking reassurance, reading something, or bringing music to listen to. Although this may not seem harmful to begin with, if you become dependent on these behaviours you can become even more distressed if one day it’s not possible to use them.

What is Bipolar Disorder?

Bipolar Disorder or Manic Depression is a mood disorder, and is the name given to the experience of abnormal moods or exaggerated mood swings. This illness is characterised by the experience of extremely “high” moods where one becomes extremely euphoric or elated, and the experience of extremely “low” moods where one becomes extremely sad and finds it difficult to experience pleasure. The high moods are called manic episodes and the low moods are called depressive episodes. These episodes can range from mild to severe and affect how a person thinks, feels, and acts. However, it is important to remember that some people may experience different patterns associated with their disorder. For example, some people may experience only one episode of mania but more frequent episodes of depression.

Bipolar Disorder occurs in approximately 1% of the population, that is, about 1 in every 100 will experience an episode that will probably require hospital care. This illness affects men and women equally, and typically begins in their early to late 20s.

Features of Bipolar Disorder

Manic Episodes

Mania is an extreme mood state of this disorder. It describes an abnormally elevated, euphoric, driven and/or irritable mood state. Hypomania is the term given to the more moderate form of elevated mood. It can be managed often without the need for hospitalisation as the person remains in contact with reality. However, it is very easy to move rapidly from hypomania into a manic episode. Symptoms of mania include:

- Irritability: Irritability as described in the Oxford dictionary means “quick to anger, touchy.” Many people, when in an elevated mood state, experience a rapid flow of ideas and thoughts. Because of this rapid thought process, they become easily angered when people don’t seem to comprehend their ideas or enthusiasm for some new scheme.

- Decreased need for sleep: One of the most common symptoms of mania and often an early warning sign is the increased experience of energy and lack of need for sleep.

- Rapid flow of ideas: People who are becoming manic experience an increase in the speed at which they think. They move more quickly from one subject to another. Sometimes thoughts can become so rapid that they begin to make no sense, developing into a jumbled, incoherent message that the listener can no longer understand. Grandiose ideas: It is common for people who are manic to think that they are more talented than others, or have unique gifts. As the person’s mood becomes more elevated, these beliefs can become delusional in nature, with people.

- Uncharacteristically poor judgement: A person’s ability to make rational decisions can become impaired and they may make inappropriate decisions or decisions that are out of character.

- Increased sexual drive: People when they become manic often experience increased libido, and may make less well-judged decisions about the sexual partners.

Depressive Episodes

Depression is a mood state that is characterised by a significantly lowered mood. Its severity, persistence, duration, and the presence of characteristic symptoms can distinguish a major depressive episode, the other extreme mood state of bipolar disorder, from a milder episode of depression. The most common symptoms of depression include:

- Persistent sad, anxious, or empty mood: People often describe depression as an overwhelming feeling of sadness and hopelessness. They may experience a loss of enjoyment in the activities of everyday life that they used to take a lot of pleasure in.

- Poor or disrupted sleep: A person when they are depressed often experience sleep disturbances, and this can be due to increased anxiety. They then find it difficult to fall asleep, or wake up frequently during the night worrying about day-to-day events or wake early in the morning and are unable to get back to sleep.

- Feelings of worthlessness or hopelessness: Sometimes people become overwhelmed with a sense of their own inability to be of use to anyone, and can become convinced that they are useless and worthless. Thoughts may revolve around the hopelessness of the situation and the future.

- Decreased interest in sex: As the person becomes more depressed, they gradually become less interested in social activities and sex.

- Poor concentration: Thinking can become slowed and the person can have difficulty in making decisions. They find it difficult to concentrate on reading a book or on the day to day tasks such as shopping. This can often create anxiety or agitation in a person.

- Thoughts of suicide, or suicide attempts: When a person becomes overwhelmed by their feelings of hopelessness and despair, they may have thoughts of ending their lives or make plans to commit suicide.

Mixed Episodes

A mixed episode is characterised by the experience of both depressive and manic symptoms nearly everyday for a period of time. The person experiences rapidly alternating moods, eg, irritability, euphoria, sadness, and there may be insomnia, agitation, hallucinations and delusions, suicidal thoughts, etc.

Diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder

Correctly identifying an illness can help you begin to explore the various treatment options available to you so that you can better manage your illness. As such, having an accurate diagnosis is the beginning of becoming well. The following diagnoses are based on the definitions and criteria used in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) by the American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

Bipolar I Disorder is the most common and prevalent of the different bipolar mood disorders. It is characterised by the experience of full-blown manic episodes and severe depressive episodes. The patterns of abnormal mood states are very varied and different individuals may experience a different course of the illness. Many physicians refer to bipolar I disorder as a relapsing and remitting illness, where symptoms come and go. It is therefore, important to ensure that treatment is continued even if the symptoms are no longer present, to prevent an episode relapse.

Bipolar II Disorder is characterised by the experience of full-blown episodes of depression and episodes of hypomania (i.e., with mild manic symptoms) that almost never developed into full-fledged mania.

Cyclothymic Disorder is characterised by frequent short periods of mild depressive symptoms and hypomania, mixed in with short periods of normal mood. Though a patient with cyclothymic disorder does not experience major depression or mania, they may go on to develop bipolar I or II disorder. Patients with bipolar I or bipolar II may experience frequent mood cycling. Patients who experience more than four episodes of hypomania, mania, and/or depression in a year are said to experience Rapid Cycling. These patients tend to alternate between extreme mood states separated by short periods of being well, if at all.

Note: A proper diagnosis should only be made by a medical doctor or psychiatrist, or a trained mental health practitioner. The information provided in this handout is not enough for an accurate diagnosis to be made by anyone who is not a trained mental health professional or physician. Please speak to an appropriate professional if you have any concerns or questions regarding the information provided here.

What Causes Bipolar Disorder?

No one factor has been identified to cause bipolar disorder, that is, it is not caused by a person, event, or experience. There are a number of factors that interact with each other that may contribute to the development of this disorder in some people. In this handout, we present to you a way of understanding how all these factors come together to trigger the onset of this illness.

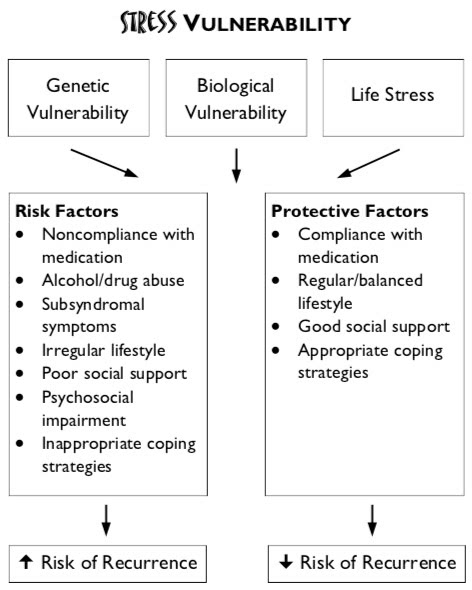

First, we begin by looking at three key factors in this model, namely: genetic vulnerability, biological vulnerability and life stress.

Genetic Vulnerability

Bipolar disorder tends to run in families. First degree relatives of people with bipolar disorder have an increased risk of developing bipolar disorder. Children of bipolar patients face an 8% risk of getting the illness versus 1% in the population. Children of bipolar patients also face an increased risk (12%) of getting unipolar depression (i.e., depression only, without mania). Identical twins are also more likely to both develop this disorder than fraternal twins. While these results indicate to some extent that this disorder is genetically inherited, they also suggest that there are other factors that may contribute to its development.

Biological Vulnerability

This refers to possible biochemical imbalances in the brain that makes a person vulnerable to experiencing mood episodes. An imbalance of brain chemicals or an inability for them to function properly may lead to episodes of “high” or “low” moods.

Life Stress

Stressful events or circumstances in a person’s life, such as, family conflicts, employment difficulties, bereavement, or even positive events, such as getting married, having children, moving house, etc, can place extra demands on the person, leading to them feeling stressed, frustrated, anxious, sad, etc. The occurrence of bipolar disorder can thus be explained as an interaction of the 3 above factors. A person who is genetically and/or biologically vulnerable may not necessarily develop bipolar disorder. These vulnerabilities are affected by how they cope with stressors in their life. For example, a person who has a family history of diabetes may not develop diabetes if they are careful with they eat and have enough exercise. This brings us to a discussion on protective and risk factors.

Protective & Risk Factors

A risk factor is something that will increase the chances of a person who is already vulnerable becoming ill. Examples of risk factors are: poor or maladaptive coping strategies, alcohol or drug use, irregular daily routines, interpersonal conflicts, stressful events, etc. Protective factors, on the other hand, are those that can help to prevent a vulnerable person from becoming ill. Protective factors include:

- good coping strategies,

- good social support networks,

- effective communication and,

- problem solving skills, etc.

It is when the risk factors outweigh the protective factors, that the chances of developing the disorder are high. This principle applies when considering the risk of recurrence as well.

Course of Illness

While some patients may experience long periods of normal moods, most individuals with bipolar disorder will experience repeated manic and/or depressive episodes throughout their lifetime. The ratio of manic episodes to depressive episodes will vary from one individual to the next, as will the frequency of episodes. Some individuals may experience only two or three episodes in their lifetime while others may experience a rapid cycling pattern of four or more episodes of illness per year. Whatever the pattern, it is important that bipolar patients learn effective ways of managing their illness and preventing the recurrence of further episodes.

Medications for Bipolar Disorder

The recognised standard treatment for bipolar disorder is medication, which focuses on controlling or eliminating the symptoms and then maintaining the symptom-free state by preventing relapse. The effective use of medication requires that you work closely with your medical practitioner. Some patients may respond well and experience few side effects with one type of medication, while others may do better with another. Thus, when taking medication, it is important that you monitor its effects and consult with your doctor.

Principles of Medication Management

- For medication to be of benefit, you should carefully follow the prescribed treatment and take note of your symptoms and side effects.

- If side effects develop, these should be reported to your doctor as soon as possible to avoid prolonged discomfort. It is strongly advised that you do not stop medication abruptly before first consulting with your doctor. This could bring on a return of a manic or depressive episode.

- Alcohol, illicit medications, and other prescribed medicines may cause your medication for bipolar disorder to be ineffective and may increase side effects. You should report all other medications and substances you are taking to your doctor to ensure that none adversely interact with the medication prescribed for bipolar disorder.

- Effective medical management of bipolar disorder requires you to monitor your symptoms and side effects, and work with your doctor to adjust dosages or types of medications.

Phases of Treatment

There are usually three phases to medical treatment for bipolar disorder. The most important aim, if you are experiencing an episode of mania, hypomania, or major depression, is to control or eliminate the symptoms so that they can return to a normal level of day-to-day functioning. The duration of this acute phase of treatment may last from 6 weeks to 6 months. Sometimes, longer periods are necessary in order to find the most effective medications with minimal side effects.

In continuation treatment, the main aim is to maintain the symptom-free state by preventing relapse, which is the return of the most recent mood episode.

The third phase, the maintenance phase, is critical and essential for all patients with bipolar disorder. The goal for maintenance treatment is to prevent recurrence, that is, to prevent new episodes of mania, hypomania, or depression from occurring. For bipolar patients, as with other medical conditions such as diabetes or hypertension, maintenance treatment may last 5 years, 10 years, or a lifetime. But remember, prolonged symptom control will help you to function better in your daily lives.

For all phases of treatment and all medications, patients must take the prescribed medication/s on a daily basis. Unlike medications like paracetamol or antibiotics that are taken only when a person actually experiences a headache or has the ‘flu, medications for bipolar disorder must be taken regularly – on both good days and bad days – at the same dosage.

Types of Medications for Bipolar Disorder

Mood Stabilisers

A mood stabiliser is a medication that is used to decrease the chance of having further episodes of mania or depression. They are the first line agents for bipolar disorder. Depending on the associated symptoms with this disorder, anti- depressants or antipsychotics may also be used. A mood stabiliser is given to a person as a maintenance medication because it regulates mood swings but doesn’t take away the cause. Feeling well does not mean you can stop taking mood stabilisers, it means the medication is keeping you stable. The most common mood stabilisers are Lithium Carbonate, Carbamazepine, and Sodium Valproate. Sometimes these medications are used on their own or in combination with other medications.

Antidepressants

Antidepressants can also be used with mood stabilisers in the acute, continuation, and/or maintenance phases of medical treatment. Thereisnooneparticularantidepressantthatis more effective than the others in bipolar disorder. In fact, there is a significant risk for antidepressants to induce or cause a “switch” to manic or hypomanic episodes, especially if a patient on antidepressants is not taking a mood stabiliser. Common antidepressants include:

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) - fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline

- Tricyclics - imipramine, amitriptyline, desipramine, dolthiepin

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) - phenelzine and tranylcypromine

Antipsychotic Medication

Antipsychotics may also be used both in the acute phase of the disorder and sometimes as a longer term treatment. Common antipsychotic agents include haloperidol, chlorpromazine, thioridazine, risperidone, and olanzapine. These medications are often combined with mood stabilisers to assist in controlling hallucinations, or delusions, to induce sleep, to reduce inappropriate grandiosity, or decrease irritability or impulsive behaviours. These medications are usually not used for treating hypomania. Although antipsychotics are most often used in treatment of the acute phase of mania, some patients may continue on smaller dosages to ensure that they do not experience a relapse of psychotic or manic symptoms.

Another often used medication is clonazepam, which is classed under the benzodiazepines. This is used as an adjunct with other medications (mood stabilisers and antipsychotics) to aid in inducing sleep, reducing psychomotor agitation, and slowing racing thoughts and pressured speech.

Remember that it is very important that you talk openly with your prescribing doctor or psychiatrist and not to stop your medication without first discussing it with them.

Psychotherapy for Bipolar Disorder

Although effective medications have been found for bipolar disorder, many patients still experience episode recurrences and relapse. Some experience between- episode symptoms that may not be serious enough to be considered a full-blown episode, but could still cause some discomfort and interference with day-to-day activities. A high rate of relapse and episode recurrences could be because of medication non- compliance, alcohol and drug use, high stress levels, many between-episode symptoms, and poor daily functioning. These issues have alerted mental health professionals to try psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions, in addition to medication, to improve illness outcome and quality of life for bipolar patients.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

A treatment approach that has been well researched for a wide range of adult psychiatric disorders is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which has recently been adapted to bipolar disorder. Although CBT for bipolar disorder is relatively new, it has been used in the treatment of a range of psychiatric disorders including unipolar depression, generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, and eating disorders. It has also been applied as an adjunctive treatment for disorders such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, personality disorders, and schizophrenia. This information package is based on this approach. CBT is a structured and time-limited intervention. It is a comprehensive psychological therapy in which there is an emphasis on collaboration between therapist and patient, and on active participation by the patient in achieving therapeutic goals.

CBT is also focused on problem solving. The central aim of CBT is to teach patients how their thoughts and beliefs play an important role in the way they respond to situations and people. The CBT approach also teaches patients the tools that could them to make their response more helpful. CBT can play a role in teaching bipolar patients about their disorder and helping them deal with adjustment difficulties. CBT can also help patients cope with everyday stressors through active problem solving, and teach patients to monitor and regulate their own thoughts, moods, and activities, and thus be prepared to manage between-episode symptoms.

Research

CBT for bipolar disorder has been evaluated in a controlled trial here at the Centre for Clinical Interventions. The results of our study showed that CBT for bipolar disorder was effective in helping patients feel less depressed and more confident about managing their illness. While this type of psychosocial treatment is still being evaluated worldwide, preliminary results from a number of studies have been positive.

Summary

Because bipolar patients experience episode recurrences and some difficulty in everyday living, some form of psychosocial treatment is recommended as an addition to medication. Recent research has found that cognitive behavioural therapy for bipolar disorder appears to be beneficial for patients. However, bipolar patients are reminded that this is an adjunctive treatment and must not be considered as a substitute for medication.

What is Depression?

Many people experiencing the symptoms of depression might begin to wonder if there is something really wrong with them. One typical fear is that they might be going crazy. Unfortunately, the reactions and comments from other people such as, “Just get yourself together!” are not very helpful.

Although you might feel alone in your struggle against depressive moods, the reality is that many people experience these moods from time to time, or even regularly. In fact, it is estimated that 1 in every 4 people experience significantly depressed mood at some time in their life.

Depression can affect any kind of person at any stage of their life. You may be an introvert or an extrovert, socially active or shy, youthful or elderly, male or female, wealthy or poor. Whatever your distinction, you can become depressed. That means that any person you know is fair game. So remember, you are not alone.

Depression is a word used in everyday language to describe a number of feelings, including sadness, frustration, disappointment and sometimes lethargy. However, in clinical practice, the term "Depression" or "Major

Depression" differs from these everyday 'down' periods in three main ways:

- Major Depression is more intense

- Major Depression lasts longer (two weeks or more)

- Major Depression significantly interferes with effective day-to-day functioning

In this handout, the word depression is referring to Major Depression or a clinical depression.

Depression as a Syndrome

A syndrome is a collection of events, behaviours, or feelings that often go together. The depression syndrome is a collection of feelings and behaviours that have been found to characterise depressed people as a group. You may find that you experience all or some of these feelings and behaviours. There are many individual differences to the number of symptoms and the extent to which different symptoms are experienced. These symptoms are described in this next section.

Mood

Depression is considered to be a disorder of mood. Individuals who are depressed, describe low mood that has persisted for longer than two weeks. In mild forms of depression, individuals may not feel bad all day but still describe a dismal outlook and a sense of gloom. Their mood may lift with a positive experience, but fall again with even a minor disappointment. In severe depression, a low mood could persist throughout the day, failing to lift even when pleasant things occur. The low mood may fluctuate during the day – it may be worse in the morning and relatively better in the afternoon. This is called ‘diurnal variation,’ which often accompanies a more severe type of depression.

In addition to sadness, another mood common to depression is anxiety.

Thinking

Individuals who are depressed think in certain ways, and this thinking is an essential feature of depression. It is as much a key symptom of depression as mood or physical symptoms. Those who are depressed tend to see themselves in a negative light. They dwell on how bad they feel, how the world is full of difficulties, how hopeless the future seems and how things might never get better. People who are depressed often have a sense of guilt, blaming themselves for everything, including the fact they think negatively. Often their self-esteem and self- confidence become very low.

Physical

Some people experience physical symptoms of depression.

- Sleep patterns could change. Some people have difficulty falling asleep, or have interrupted sleep, others sleep more and have difficulty staying awake

- Appetite may decline and weight loss occurs, while others eat more than usual and thus gain weight

- Sexual interest may decline

- Energy levels may fall, as does motivation to carry out everyday activities. Depressed individuals may stop doing the things they used to enjoy because they feel unmotivated or lethargic

Interacting with Other People

Many depressed people express concern about their personal relationships. They may become unhappy and dissatisfied with their family, and other close, relationships. They may feel shy and anxious when they are with other people, especially in a group. They may feel lonely and isolated, yet at the same time, are unwilling or unable to reach out to others, even when they have the opportunities for doing so.

It is important to understand that depression is not caused by one thing, but probably by a combination of factors interacting with one another. These factors can be grouped into two broad categories – biology and psychology. Many biological and psychological factors interact in depression, although precisely which specific factors interact may differ from person to person.

Biological Factors

The biological factors that might have some effect on depression include: genes, hormones, and brain chemicals.

Genetic Factors

Depression often runs in families, which suggests that individuals may inherit genes that make them vulnerable to developing depression. However, one may inherit an increased vulnerability to the illness, but not necessarily the illness itself. Although many people may inherit the vulnerability, a great many of them may never suffer a depressive illness.

Hormones

Research has found that there are some hormonal changes that occur in depression. The brain goes through some changes before and during a depressive episode, and certain parts of the brain are affected. This might result in an over- or under-production of some hormones, which may account for some of the symptoms of depression. Medication treatment can be effective in treating these conditions.

Brain Chemicals (Neurotransmitters)

Nerve cells in the brain communicate to each other by specific chemical substances called neurotransmitters. It is believed that during depression, there is reduced activity of one or more of these neurotransmitter systems, and this disturbs certain areas of the brain that regulate functions such as sleep, appetite, sexual drive, and perhaps mood. The reduced level of neurotransmitters results in reduced communication between the nerve cells and accounts for the typical symptoms of depression. Many antidepressant drugs increase the neurotransmitters in the brain.

Psychological Factors

Thinking

Many thinking patterns are associated with depression. These thinking patterns include:

- overstressing the negative

- taking the responsibility for bad events but not for good events

- having inflexible rules about how one should behave

- thinking that you know what others are thinking and that they are thinking badly of you

Loss

Sometimes people experience events where loss occurs, and this can bring on depression. The experience of loss may include the loss of a loved one through bereavement or separation, loss of a job,loss of a friendship, loss of a promotion, loss of face, loss of support, etc.

Sense of Failure

Some people may stake their happiness on achieving particular goals, such as getting ‘As’ on their exams, getting a particular job,earning a certain amount of profit from a business venture, or finding a life partner. If for some reason they are not able to achieve those goals,they might believe that they have failed somehow, and it is this sense of failure that can sometimes bring on, or increase, depression.

Stress

An accumulation of stressful life events may also bring on depression. Stressful events include situations such as unemployment, financial worries, serious difficulties with spouses, parents or children, physical illness, and major changes in life circumstances.

Conclusion

While we cannot do much about the genes we have inherited, there are a number of things we can do to overcome depression, or to prevent us from becoming depressed. Your doctor may have suggested medication, especially in a severe depression. While taking medication can be of assistance in overcoming depression, psychological treatments are also available. Ask your doctor or mental health practitioner for more details.

Psychotherapy for Depression

Depression can be treated with medical treatments such as antidepressant medication or electroconvulsive therapy, and psychotherapy. Please see your medical doctor or psychiatrist for more information about medical treatments as this will not be discussed in this handout.

We’re now going to talk briefly about two psychological therapies that have been proven to be effective most of the time. You might have come across words such as “best practice” “evidence-based practice,” “evidence-based treatment” or “evidence-supported therapy.” These words refer to a particular type of treatment or therapy that has been evaluated and has proven to be effective. For the treatment of depression,the evidence-supported therapies include cognitive therapy and behaviour therapy.

Cognitive Therapy

The aim of cognitive therapy is to help individuals realise that they can influence their mood by identifying and changing their thoughts and beliefs. When people are depressed, they often think very negative thoughts about themselves, their lives, and their future. This further worsens their mood. Cognitive therapy focuses on discovering and challenging unhelpful assumptions and beliefs, and developing helpful and balanced thoughts. Cognitive therapy is also structured, time-limited, and focused on the ‘here-and-now.‘ This form of treatment for depression has been proven to be effective when individuals are able to acquire the skills that are being taught in therapy.

Behaviour Therapy

Depressed people tend to feel lethargic and unmotivated. They often stay at home and avoid going out and interacting with people. As such, they may miss out on opportunities that help lift their mood. Behaviour therapy aims to identify and change aspects of behaviour that may perpetuate or worsen the depression. Some behavioural strategies include: goal setting, activity scheduling, social skills training, and structured problem solving.

In Summary

These two therapies have been shown to be effective most of the time. Often, a combination of these therapies are offered for people who experience depression. This information package focuses on providing information on the cognitive and behavioural aspects of depression, which includes suggested strategies for how you could better manage your mood.

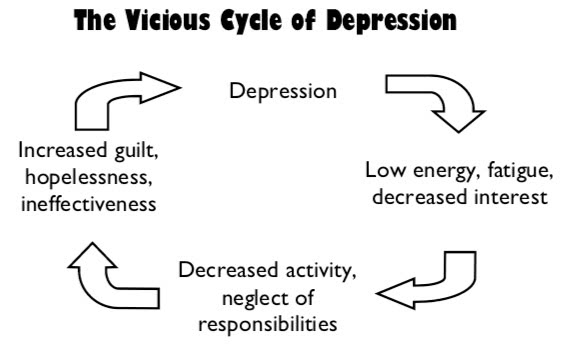

The Vicious Cycle of Depression

The symptoms of depression can bring about some drastic changes in a depressed person’s life, daily routines, and their behaviour. Often it is these changes that makes the depression worse and prevents the depressed person from getting better. For example, a lack of motivation or a lack of energy can result in a depressed person cutting back on their activities, neglecting their daily tasks and responsibilities, and leaving decision-making to others. Have you noticed these changes in yourself when you are depressed? You may find that you have become less and less active, don’t go out much anymore, avoid hanging out with friends, and stopped engaging in your favourite activity. When this happens, you have become locked in the vicious cycle of depression, which might look like this:

The Vicious Cycle of Depression

When your activity level decreases, you may become even less motivated and more lethargic. When you stop doing the things you used to love, you miss out on experiencing pleasant feelings and positive experiences. Your depression could get worse.

Similarly, when one begins neglecting a few tasks and responsibilities at work or at home, the list may begin to pile up. As such, when a depressed person thinks about the things they have to do, they may feel overwhelmed by the pile of things they have put off doing. This may result in them feeling guilty or thinking that they are ineffective or even, a failure. This will also worsen the depression.

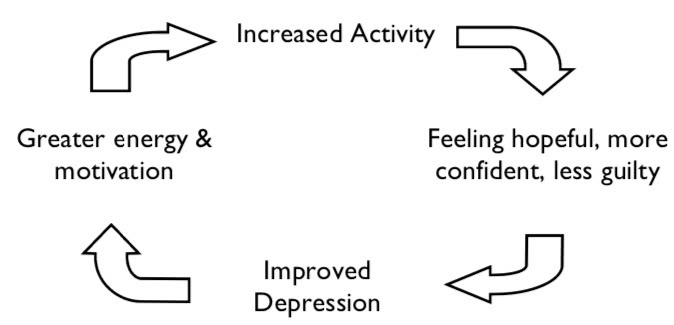

Reversing the Vicious Cycle of Depression

One of the ways of breaking the vicious cycle of is through the use of medication. Medication such as antidepressants can help change your energy level and improve sleep. Another way is to simply increase your activity level, especially in pleasurable activities and tackling your list of tasks and responsibilities, but doing it in a realistic and achievable way, so that you set yourself up to succeed.

Becoming more active has a number of advantages:

- Activity helps you to feel better

- Activity helps you to feel less tired

- Activity can help you think more clearly

When the depression cycle is broken, it will look like this:

Reversing The Vicious Cycle of Depression

Here’s a list of possible fun things to do. You can add your own to this list.

- Soaking in the bathtub

- Collecting things (coins, shells, etc.)

- Going for a day trip

- Going to see a comedy at the movies

- Going to the beach

- Playing squash/tennis/badminton

- Having a barbecue at the park

- Going for a walk, jog, or hike

- Listening to uplifting music

- Gardening

Try some of them out and evaluate how you feel before and after the activity. Chances are, you’ll find that you’ll feel a little better. The important thing is to persist – keeping your activity levels up is the first step to breaking out of that vicious cycle! The second step is to look at how thinking patterns contribute to the vicious cycle of depression. The “Improving how you feel” information sheet starts to look more closely at this.

Grief and Bereavement

Uncomplicated Grief

Grief and loss are part of life and is experienced by most of us at some point in life. People deal with grief in many different ways, and not necessarily going through a predictable group of ‘stages,’ although some do. How people grieve can depend on the circumstances of the loss (e.g., sudden death, long illness, death of a young person) as well as past experiences of loss. There is no time limit on grief - some people get back to their usual routine fairly quickly, others take longer. Some people prefer time alone to grieve, others crave the support and company of others. Below are just some of the range of experiences which can be part of uncomplicated grief:

- Symptoms of depression or anxiety, such as poor sleep, lowered appetite, low mood, feeling of anxiety - for some people the anxiety will be more obvious, for others the depression.

- A sense of the loss not quite being ‘real’ at first, or refusal to believe it has occurred

- Feeling disconnected from others, sense of numbness

- Guilt about not initially feeling pain about the loss

- Worries about not grieving ‘normally’ or ‘correctly’

- Mood swings and tearfulness

- Guilt about interactions with the person who has died (e.g. I should have spent more time with her or I wish we didn’t have that argument)

- Waves of sadness or anger which can be overwhelming and sometimes suddenly triggered by reminders

- Seeking reminders of the person who has died, e.g. being in their home or with their belongings, or perhaps at times even feeling you see or hear the deceased person

- Guilt about gradually getting back to ‘normal’ life and at times not ‘remembering’ to feel sad

Coping with Uncomplicated Grief

Most people going through the pain described above will eventually adjust to the loss and return to normal life, although of course carrying some sadness about the loss. Most people do not require medication or counselling to manage uncomplicated grief, and should simply be supported to go through their individual grief process. It is important to maintain a healthy diet and some physical activity during this time. Some people may find it helpful to engage in counselling or to attend groups with others who have suffered a recent loss.

Complicated Grief

Complicated grief is a general term for describing when people adjust poorly to a loss. This is very difficult to define, as there is no standard which limits what is normal or healthy grief.

Below are some warning signs which may suggest that a person is not coping well with grief and may be at a greater risk of the grieving process taking longer to resolve or being more difficult:

- Pushing away painful feelings or avoiding the grieving process entirely

- Excessive avoidance of talking about or reminders of the person who has died

- Refusal to attend the funeral

- Using distracting tasks to avoid experiencing grief, including tasks associated with planning the funeral

- Abuse of alcohol or other drugs (including prescription)

- Increased physical complaints or illness

- Intense mood swings or isolation which do not resolve within 1-2 months of the loss

- Ongoing neglect of self-care and responsibilities

Again, it is important to emphasise that there are no ‘rules for grieving’ and that many of the items above may occur as part of uncomplicated grief. However, people who are coping very poorly one month after a loss may continue to cope poorly 1-2 years later, so if these warning signs are present then it is often worthwhile seeking some help early on, to increase the chances of adjusting in the long term.

Coping with Complicated Grief

Psychological therapy can support people to safely explore feelings of grief and connect with painful feelings and memories, paving the way for resolution. Therapy may also support people to use strategies such as relaxation, engaging in positive activities, and challenging negative thoughts, in order to combat the associated symptoms of anxiety and depression. Antidepressant medication may also be used to alleviate depression associated with grief, and this can be useful in conjunction with psychological strategies. Tranquilizing medications can interfere with the natural grieving process. Although early help is recommended, health professionals are able to support people to work through complicated grief even years after the loss.

What is Anger?

Normal Anger

Anger is a normal human emotion. Everyone feels annoyed, frustrated, irritated, or even very angry from time to time. Anger can be expressed by shouting, yelling, or swearing, but in extreme cases it can escalate into physical aggression towards objects (eg. smashing things) or people (self or others). In some cases, anger might look much more subtle, more of a brooding, silent anger, or withdrawal. In a controlled manner, some anger can be helpful, motivating us to make positive changes or take constructive action about something we feel is important. But when anger is very intense, or very frequent, then it can be harmful in many ways.

What Causes Anger?

Anger is often connected to some type of frustration— either things didn’t turn out the way you planned, you didn’t get something you wanted, or other people don’t act the way you would like. Often poor communication and misunderstandings can trigger angry situations. Anger usually goes hand-in-hand with other feelings too, such as sadness, shame, hurt, guilt, or fear. Many times people find it hard to express these feelings, so just the anger comes out. Perhaps the anger is triggered by a particular situation, such as being caught in a traffic jam, or being treated rudely by someone else, or banging your thumb with a hammer while trying to hang a picture-hook. Other times there is no obvious trigger—some people are more prone to anger than others. Sometimes men and women handle anger differently, but not always.

Problems Associated With Anger

Uncontrolled anger can cause problems in a wide range of areas of your life. It may cause conflicts with family, friends, or colleagues, and in extreme situations it can lead to problems with the law. But some of the other problem effects of anger may be harder to spot. Often people who have a problem with anger feel guilty or disappointed with their behaviour, or suffer from low self-esteem, anxiety, or depression. There are also physical side-effects of extreme or frequent anger, such as high blood pressure, and heart disease. Some studies suggest that angry people tend to drink more alcohol, which is associated with a wide range of health problems.

Do I Have a Problem with Anger?

Perhaps you have already identified that anger is a problem for you, or someone else has mentioned it to you. But if you are not sure whether anger is a problem for you, consider the following questions:

- Do you feel angry, irritated, or tense a lot of the time?

- Do you seem to get angry more easily or more often than others around you?

- Do you use alcohol or drugs to manage your anger?

- Do you sometimes become so angry that you break things, damage property, or become violent?

- Does it sometimes feel like your anger gets out of proportion to the situation that set you off?

- Is your anger leading to problems with relationships, such as with family, friends, or at work?

- Have you noticed that others close to you sometimes feel intimidated or frightened of you?

- Have others (family, friends, colleagues, health professionals) mentioned that anger might be a problem for you?

- Do you find that it takes you a long time to ‘cool off’ after you have become angry or irritated?

- Have you ended up in trouble with the law as a result of your anger, for example getting into fights?

- Do you find yourself worrying a lot about your anger, perhaps feeling anxious or depressed about it at times?

- Do you tend to take your frustration out on loved ones or people less powerful than you, rather than dealing with the situation that triggered your anger?

If you answered ‘yes’ to any of these questions, it may be that anger is a problem for you. It may be that addressing your anger can allow you to live a much more positive and rewarding life.

How Can I Manage Anger Better?

You may have heard about ‘anger management’ and wondered what it involves. Anger management can be addressed in groups or through individual therapy, and there are also a lot of self-help resources available. Anger management is not just about counting to ten before you respond (although that is often a good idea). It is about helping you to better understand why you get angry, what sets it off and what are the early warning signs, and about learning a variety of strategies for managing those feelings more constructively. You may wish to read through our ‘Anger Coping Strategies’ handout for more information about this.

Anger Coping Strategies

Anger and Problem Anger

Anger is a normal human emotion, and can range from mild irritation to an intense rage or fury. Our handout ’What Is Anger?’ provides more detail about the difference between normal anger and problem anger, and some questions to help you identify whether anger may be a problem for you. This handout includes a number of tips which you may use to help you to cope better with your anger. You may wish to practice some of these on your own, or you may wish to combine them with individual or group therapy for extra support.

Triggers and Early Warning Signs

One of the first steps in managing your anger is to identify what types of situations usually trigger your anger. Make a list of the things which usually set you off, for example:

- being cut off in traffic

- running late for an appointment

- other people running late

- your son/daughter leaving their schoolbag in the hall

- your partner not putting away the dishes

- a colleague falling behind on a project

Some of these situations you may be able to avoid, such as planning ahead to avoid running late. Other situations are less in your control, such as being cut off in traffic, but what you can control is your response. Once you have finished listing your common trigger situations, make a separate list of the warning signs for your anger. What is it that usually happens in your body when you get angry? Becoming aware of your body’s alarm bells helps you to spot anger early on, which gives you a better chance of putting other coping strategies into practice. Some common warnings are:

- tightness in chest

- feeling hot or flushed, sweating

- grinding teeth

- tense muscles or clenched fists

- pounding or racing heart

- biting your nails

Why Am I Angry?

When you notice these warning signs, stop and ask yourself what it is that is making you angry. Often there will be something going on that is quite reasonable to feel angry about, so allow yourself to acknowledge this. But it is also important to be clear about the cause of our anger so that we don’t respond in a way that is out of proportion (eg. staying angry all day about someone else using up the last of the milk) or take out the anger on the wrong person (eg. getting angry at family members when it is your boss you are angry with).

Taking Out The Heat

When you notice yourself becoming angry, there are a number of techniques which you can use to ‘take the heat out’ of your anger. These include:

Time Out: This simply means removing yourself from the situation for a period of time, to give yourself a chance to ‘cool down’ and think things through before you act. For example, when you notice yourself becoming angry during an argument with your partner, say “I need to take time out, let’s talk about this calmly when I get back” and then go for a walk.

Distraction: If you cannot change the situation, it can help to distract yourself from whatever is making you angry by counting to ten, listening to music, calling a friend to chat about something else, or doing housework. For example, if you are stuck in traffic and getting angry, put on the radio and try to find a song you like, or count the number of times the chorus is sung.

Silly Humour: While it is not always possible to just ‘laugh your problems away,’ you can often use humour to help you to take a step back from your anger. For example, if you are angry with a colleague and refer to them as ‘a stupid clown,’ think about what this means literally. Imagine or draw them dressed in a clown suit, with big shoes and a red nose. If you picture this image every time they do something which bothers you, it will be much easier to keep things in perspective.

Relaxation: Just as our bodies are strongly affected by our emotions, we can also influence our emotional state with our physical state. Relaxation techniques, such as taking slow deep breaths or progressively tensing and relaxing each of your muscle groups, can help to reduce anger.

Self-Talk and Helpful Thinking

How you are thinking affects how you are feeling, so focussing on negative thoughts such as “this is so unfair” will maintain the angry feeling. Make a list of more balanced statements you can say to yourself before, during and after difficult situations. For example: Before: I know I can handle this, I have strategies to keep my anger under control and can take time out if I need to. During: Remember to keep breathing and stay relaxed. There is no need to take this personally. I can manage this. After: I handled that well. Even though I felt angry I didn’t raise my voice too much and I think I got a better result

Assertiveness and Practice

Another key strategy in managing anger is to learn to be assertive. Assertiveness means expressing your point of view in a clear way, without becoming aggressive. You may wish to read other handouts about this topic. Finally, because anger is often an automatic response, all of these techniques require a lot of practice.

Facts About Sleep

The Nature of Sleep

Sleep is such an important part of our lives, yet many of us don’t pay much attention to it. It is usually not until we have problems with sleep that we notice it and start to try to understand the nature of sleep. As well as humans, other mammals, reptiles and birds all sleep, while fish, amphibians and insects do not (although they may rest). Some animals sleep in many short bursts, while others, like humans, prefer to sleep in one long block.